I blame Doctor Who. It’s my earliest memory of watching television.

To quote Wikipedia: “Doctor Who is a British science fiction television series broadcast by the BBC since 1963. The series, created by Sydney Newman, C. E. Webber and Donald Wilson, depicts the adventures of an extraterrestrial being called the Doctor, part of a humanoid species called Time Lords. The Doctor travels in the universe and in time using a time-travelling spaceship called the TARDIS, which externally appears as a British police box. While travelling, the Doctor works to save lives and liberate oppressed peoples by combating foes. The Doctor often travels with companions.”

Of the 15 actors who have portrayed the Doctor on TV, Patrick Troughton made the deepest impression. He was the second Doctor (after William Hartnell) and played him as an eccentric cosmic hobo who wore tartan trousers and blew a recorder. The late chess master Michael Basman would also have been convincing in the role.

What has Doctor Who to do with chess? One of the things that first drew me to the game was its time-travelling quality. It was a direct link to the past; to be sat pondering the very same chess position that had puzzled the Great Masters hundreds of years ago – wow! Chess was a kind of TARDIS. I could be a Time Lord too!

Apart from sparking an interest in the game’s history, this sense of wonder may explain why so much of my opening repertoire is still rooted in the early twentieth century.

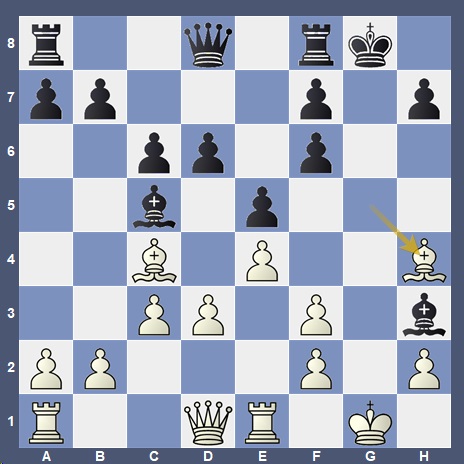

All this crossed my mind as I was playing Will Burt last week. We reached this position after eight moves:

Jon Manley v Will Burt

Oxford City 1 v Cowley 1, Oxford League Division 1

The opening was the venerable Four Knights’ Game. It was all the rage in the 1900s; chess legends Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Marshall and Tarrasch all reached this position.

White’s challenge is to break the symmetry and get a small advantage. What’s to stop Black simply copying White’s moves and making an early draw?

I remembered that this position is discussed in How to Play the Chess Openings by the fabulously named Eugene Znosko-Borovsky. This book was essential reading for chess players in the 1940s and Dad had given me his copy when I was a schoolboy. I could picture its green mildewed cover but couldn’t for the life of me recall any of its advice about the position. Damn!

This is what it has to say:

“The Four Knights’ Game is one of the quietest [openings]. White temporarily renounces the initiative and strives above all for the development of his pieces, Thus, move after move, the position is for a long time in equilibrium, and is sometimes even symmetrical.

But Black may fall into the mistake of believing that he can unthinkingly continue to repeat White’s moves. But as soon as White makes a slightly aggressive move, Black must abandon the symmetry or he will automatically suffer disaster.” (pp.46-7)

All well and good, but what’s White’s best try here?

He has four plausible ‘slightly aggressive’ moves – two captures, a capture with check and a fork:

9 Nxb4, 9 Bxf6, 9 Nxf6+ and 9 c3

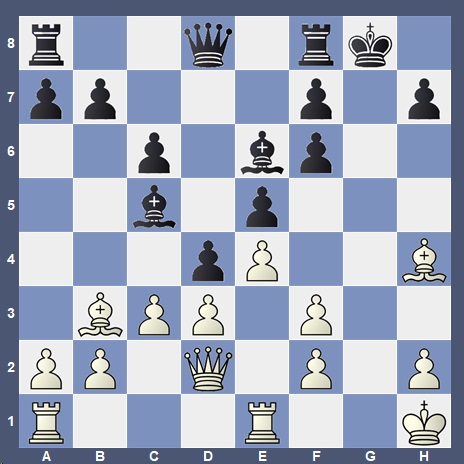

After a while I chose the quiet 9 Bc4, challenging Will to be the first to deviate, but he declined with

9…Bc5

Time for White to be more aggressive.

10 c3

Now, following Znosko’s advice, Black must break the symmetry because 10…c6? would lose a piece to 11 Nxf6+ gxf6 12 cxd4.

10…Nxf3+ 11 gxf3 Bh3 12 Re1 c6 13 Nxf6+ gxf6

Now White can invite a return to symmetry with 14 Bh6, which was the choice of the famous attacking master Rudolf Spielmann. In that game his opponent gave up the exchange by 14…Kh8 15 Bxf8 Qxf8 with an eventual draw (Spielmann-Teichmann, San Sebastian 1912).

Will Burt is a dangerous player who will sacrifice the exchange in the blink of an eye. So rather than wave a red flag with 14 Bh6 I played

14 Bh4

The computer likes this move as it keeps an eye on Black’s main weakness, his f6 pawn.

14…d5 15 Bb3 d4?

A mistake because it loses time and exposes Black’s f7 pawn. His best plan is …Kh8 and …Rg8 immediately.

16 Kh1 Be6?? 17 Qd2

Suddenly Black is defenceless against White’s invasion on the g-file.

17…Kh8 18 Qh6 Be7 19 Rg1 Rg8 20 Rxg8+ Qxg8 21 Rg1 1-0

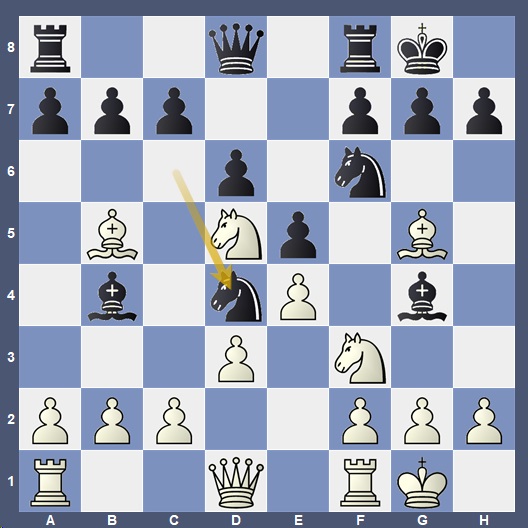

This still leaves the question: what’s White’s best move in this position?

All Znosko says in his book is that Black should avoid it altogether and deviate two moves earlier.

What about the Greats? Capablanca tried 9 Nxb4, and Alekhine 9 Kh1 (a bit tame for him). Meanwhile Tarrasch and Marshall were happy defending the black side against weaker opponents. Unable to take a spin in the TARDIS to seek their opinion. I asked Stockfish instead. Strangely the engine recommends 9 c3 and continuing the imitation game:

9 c3 c6 10 Nxf6+ gxf6 11 Bh6 Nxf3+ 12 gxf3 Bh3 13 Re1 Re8 14 f4 f5 15 Kh1 Kh8 16 Rg1 Rg8 17 Bc4

Now 17…Bc5 fails to 18 Qh5! Bg4 19 Rxg4 fxg4 20 Bxf7, so Black has to try the queen manoeuvre himself.

17… Qh4 18 Bg5 Rxg5 19 fxg5 Bc5 20 d4! with a clear advantage to White.

All hail Stockfish, our sonic screwdriver!